Note: This interview was originally published in the Sophia: The Journal of Traditional Studies (volume 16 no. 1, December 2020).

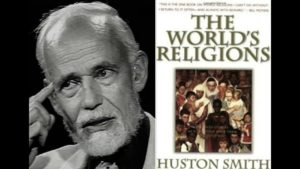

The following dialogue is taken from a set of interviews with Huston Smith conducted by Terry Moore in 2008 and 2009.

TM: Dr. Smith, I understand that you have recently decided to publish your autobiography. I remember some time ago you said that an autobiography was not something you ever intended to publish. What changed your mind?

HS: Yes, I remember that! I was determined not to publish an autobiography. But last year I was persuaded by a number of people, mostly my friend Pico Iyer –who has written so wonderfully about his own journeys and about the Dalai Lama—persuaded me that I had a story to tell that would be interesting and, possibly, helpful to others who were interested in the wisdom of religion and who may find my experiences helpful in their own journey.

The other thing that persuaded me to change my mind with finding a suitable title, for which I must thank my wife, Kendra.

TM: And the title?

HS: “Tales of Wonder and Deep Delight.” It’s from the poem by Robert Penn Warren:

Tell me a story.

In this century, and moment, of mania,

Tell me a story.

Make it a story of great distances, and starlight.

The name of the story will be Time,

But you must not pronounce its name.

Tell me a story of deep delight.

TM: Dr. Smith, one of the areas you have written much about is the relationship between religion and science. This seems to be getting a lot of attention these days. What do you see as the essential difference between the scientific and the religious viewpoint?

HS: Religion, even though it has to have a worldview which covers everything, cannot detail the specifics of the physical universe with the exactitude that science can. And therefore as Oliver Wendell Holmes said, “Science gives us major answers to minor questions; religion gives us minor answers to major questions.”

That’s one of the balances re-established. It’s a level playing-field.

TM: One of the reasons that science is so interesting here is that first of all it is very powerful; second, it is very much part of the culture; third, there are a lot of very good minds in science; and fourth, a lot of those very good minds seem to be confronting the awe and majesty of the great religions. From my view, I see a lot more of that in science than I do in philosophy or in religion, from the point of view of the Academy, the people who are studying. So often the people in the philosophy department, or who have studied comparative religion, seem to be more interested in learning what other people thought, or memorizing and presenting classical arguments, while the people in the sciences are having that “Aha!” experience of discovery. I see more of that in science than I do in religion and philosophy.

HS: I think that’s probably an accurate perception because science is the king-pin among the intelligentsia. And a part of my critique of science is that it has seduced first the social sciences—I’ve always thought that was a dubious name—and then academia in general. And one can almost say—I will say it, though I’m not absolutely sure—that the less secure a discipline is, the more it tries to jack up its reputation by aping the sciences, with disastrous results.

TM: That would describe a lot of the social sciences.

And I’ve talked about the American Academy of Religion, and on balance, it’s terrible. Because you’re right: that academy approaches religion from the angle of the social scientists, and their methodology is totally secular.

TM: I know there are a number of enterprises that are attempting to deal with this issue, or “balance” it as you say. One of them is the Templeton Foundation; another is the Center for Theology and Natural Science. What do you make of this effort?

HS: Templeton, in my view always seems to give primacy to science and then tries to demonstrate that religion is in some way “scientific.”

The Center for Theology and Natural Science is a little different. CTNS is concerned with that too, and they are open—I won’t say that they’re closed—but I think that they want to maintain their credentials with their discipline. And for that reason I think they tailor their thinking, the issues they discuss in their papers and their books, too much in the direction of how much theology can we translate into scientific terms.

TM: That’s similar, but a little different.

Yes, they try to jam so much theology into the duffel-bag of science, but they would insist that it cannot accommodate all of theology. So they’re right in that. But as for their on-going efforts at their monthly meetings, open meetings—I used to go for about a decade to them very regularly. But I’ve given up, because once you acknowledge—and I’ll put it in the theological language that they use—that God exists, and the second point that he/she/it (the pronouns never work, and that is still to say nothing about the “Godhead”) can intervene in the natural laws, then what’s there to talk about? Well, it’s interesting to see how much can be rephrased, but it ceases to be important. And so I still out of friendship pay my $35 a year membership dues to support the organization, but I no longer go to their meetings, because I have more interesting things to do, for me.

TM: In what other efforts are you involved in this area?

Now, one other thing. The kind of dean of the science-theology dialogue, who received the Templeton Prize for a million dollars, a few years back—very good friend of mine, Ian Barbour. He and I have sort of grown up together. But his whole vocation is to write on this subject. Let me add here that my research is every bit as good as his here; my shelf of books on science (for the layman, not the technical textbook) is as long as the shelves on any of the eight religions that I deal with in the world’s religions.

The trouble with my friend Ian is that he is one of the two most “Christian Gentlemen” that I know: even though we disagree, he is always very courteous. But it’s to a fault. Because more and more I’ve grown tired of reading him, because he pacifies. He discusses one way of looking at things, then another way of looking at things, then yet another way, and on and on and on: slicing the cheese. And sure, there are many ways to do it. But he rarely tips his own hand. He’s a kind of historian of the latter twentieth century.

TM: Are there people in the sciences with whom you have had specific issues?

HS: Yes, a good example is Ursula Goodenough, who’s a cell biologist. I take her to task for a section, as she wrote a book on the sacred depths of nature. She has a great feeling and awe and wonder—all of that—but she says flat out there is no mind that has put this in place and is monitoring this. You can read this exchange in a journal called Zygon which is devoted entirely to this science-religion debate/discussion. But again, it leans way too much towards science. And they get very technical and so on. I’d suggest Ian Barbour’s book, and Zygon, if you want to be on top of the issue. There’s also one in Philadelphia, the Center for Research on Science and Religion, but it operates entirely on whim.

TM: This tendency of modern scholars to approach one discipline solely on the terms of another discipline—as you say,“ jamming theology into the duffel-bag of science, or into the duffel-bag of history, for that matter—reminds me of the work you’ve done in the study of cultural myth. Today, myth is usually studied as history or sociology—but not as theological or cosmological truth. I remember that you were a good friend of Joseph Campbell, who is also well known for his work in this area. Can you speak about the differences between your approach and his approach to the study of myth?

HS: Let me tell you about the two sides of the street. “Myth” is the name of the street. And Joseph and I agreed early on that we would work the same street, but different sides. He would work the side of the power of myth and psychology. And I would work the side of the truth of myth, and the philosophy, theology—actually neither of those terms is quite accurate—the metaphysics of myth is probably more accurate. Joseph was too bruised by his Irish Catholic up-bringing—too wounded really—to believe these myths. But he just realized the power of them.

Now I’m going to tell you my favorite anecdote about Joe Campbell. Stop me if I’ve already done that—what I dislike most is people tolerating my story that they’ve already heard them many times before. Kendra warns me on that.

OK. Once in the corridor of O’Hare airport, well we almost collided. I used to say that sooner or later you meet everybody in a corridor at O’Hare. Now maybe it’s Atlanta. We greeted each other happily, looked at our watches, and found we had just enough time to have a sandwich together before going to our respective planes. He was coming back from a lecture tour in the Bay area, and I was on my way to it. And this is the story he told me.

He said he told his host, “Don’t meet me at the plane; I’ve got friends all over the place. I’m going to rent a car. Just tell me where my first appointment is.” Well, it turned out to be a synagogue somewhere in Marin. He wanted to be sure he wasn’t late, so he got there about half an hour early, identified the location. He parked a reasonable distance from it, got out of his car, locked it, and as he was walking towards the synagogue, a little boy about six years old said, “You can’t park here.” And Joe looked around and said, “Well, why can’t I? I do not see any red on the curb, and I don’t see any “No Parking” signs. Why can’t I park here?” And the boy said, “Because I’m a fire hydrant.”

Now, this is why I’m telling this story. You know what Joe did? He said, “Ooh, thank you. I could have gotten a ticket.” He went back, unlocked his car, backed it up fifty feet, and he parked it. And as we were leaving the lunch, going to our respective departure gates, I found myself thinking, if there was anybody on this planet who could understand a six-year-old boy who was a hydrant, that would be Joe Campbell.

Wonderful friend. Handsome, articulate, and basically right. What he did I think was to underscore that there is a positive meaning for myth as well as a negative, like the myth of the Super-Race. In that sense, myth is error. But he brought out and caused, I think, almost single-handedly made us understand that myth has two sides, a down- and an up-side. And that’s no small achievement for a lifetime.

TM: Dr. Smith, I recently saw the video you did on “Dying and Transformation.” Knowing that you will be 91 this year, may I ask what you think about death?

I have no fear of death, but I do confess that I have an inordinate fear of unrelievable pain. But with the medications now, that can be taken care of. And the other one is, and I have to work on this, I have a fear of being dependent. Now I have been dependent, truth to tell, on Kendra practically all our married life, but it has gotten more and more. And I think I am at peace with that.

I don’t think we can ever tell, predict, when the hatchet, or guillotine comes, how we will react. I have a wise friend, a poet, who was a Fusilier [the friend is actually Robert Graves the English poet], and he said, “We can never predict when courage is needed, whether we will have it or whether we will be just terrified.” He said, “I was in a danger-of-death situation, and one time I acted with extraordinary courage, just didn’t think about anything else except what had to be done; and the other time I just virtually turned tail.” So that was his point: we cannot tell. And I introduced that because when the moment of death comes, from this distance I can honestly say that I would love to have my family around me, and then just stop breathing. But when that situation comes, I don’t know how I will react.

After we had finished a very pleasant dinner, and sort of pushed our chairs back for conversation, why, my friend opened up and said, “Gentlemen, what do you have against ghosts?” Well, I had a hard-nosed chairman of my department, and only science and everything, and when he said, “What do you gentlemen have against ghosts?” I thought this chairman was going to choke on his brandy. But he caught himself, but immediately deflected the question, saying, “I love your love of poetry.”

And my friend described a situation when in World War II he was trapped in a flaming tank and by all statistical probability he should have been burned to death—miraculously he survived. And we said, “Well, that must have been just terrifying!” And he said, “On the contrary. It was ecstatic.”

I don’t know what to make of that. But it’s interesting, and more than interesting.